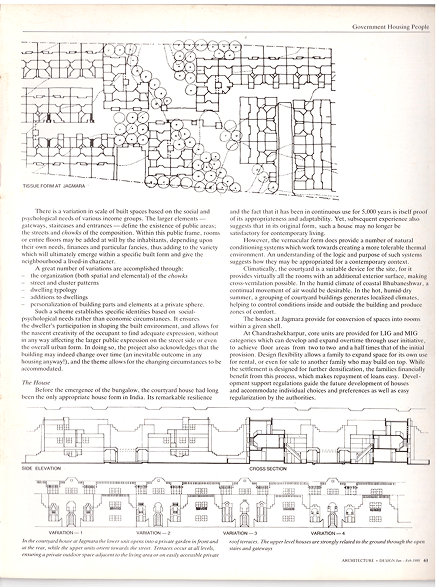

Hierarchies, Networks and Linkages

The ordering of space resulting from a top-down translation of scale levels establishes the necessary hierarchy in space organization. Leading from the doorstep upward, one could find multiple choices built into the system for circulation and contact, characterized by networks. Hierarchy establishes the required order and clarity in desegregation of space and familiarity for all, while the network offers choices to inhabitants based on personal preferences-having to do with cultural, social or climatic considerations. Thus an autonomous system could coexist with an external order necessitated by town planning requirements or vehicular circulation.

Social Organization of Space and Built Form

This social organization of space could be used as a fundamental unifying element of the neighborhood in such a manner that private and public ownership to territory becomes subordinate to social and personal spaces occurring in the hierarchical network. Personalization (as different from privatization) of public spaces, elements, and even facilities becomes an important aspect of design. Design in turn could begin to establish its own boundaries which are different from the territorial imperatives established through money transaction.

The more involved a person is in the shaping and maintenance of his surroundings, the more appropriate they become and the more easily appropriated ‘by him; but just as he takes possession of his surroundings so will they also take possession of him. This care and solicitude create a situation in which a person appears to be needed by his surroundings. Not only does he have some control over them but they in turn are a reflection of him, and have some control over him too. 12The crucial point is to appreciate the fact that while respect for personal initiatives is important, it should occur within a social frame, with established ground rules.

Notion of Equity

Charles Correa raises a fundamental issue when he proclaims that “Most planning today, no matter how liberated its intentions, ends up with a rigid caste system of residential areas as witness Chandigarh”. If one has to operate on the basis of different plot sizes, their positioning would imply rigid and inflexible exclusive pockets of social class instead of an organic mix of incomes and communities, it is argued.

The notion of equity, however, is not restricted to reducing the difference in size between very small and unusually large plots. Equity should also be understood as offering equal and easy access to all facilities and comparable linkages of parts with the whole irrespective of social group.

The Regressive Idea of the

“SMART CITY”

CHALLENGES FOR THE HABITAT III URBAN AGENDA

NEW URBANISM

one more claimant among the many floating around..

We live in a condition of upheaval. Existing places are subject to conflicting aspirations; undefined spaces even more so. Those who run the city dream of a global metropolis, in thrall to its image, oblivious of the process of its manufacturing. Investors see a slot machine for the faster reproduction of money. Those who service the city want their position unthreatened. Communities seek autonomy, while those who do not have a stake would hold it under siege because of the contempt with which others view their welfare.

The city in this landscape seems made up of irreconcilable parts. The city becomes a turf on which sectarian interests fight and negotiate space. It is only the old-fashioned dualist who will attempt to explain it in terms of the ‘planned’ and the ‘unplanned’. The multiplist knows it is many fragments, the divides dependent upon the conceptual framework within which the viewer works.

With globalization, the affluent raise the bar on consumption and architecture becomes indulgent. This image of the architect almost as a puppeteer has infected mass consciousness, as in the ‘Matrix’ trilogy. Meanwhile, others struggle to find shelter, work, basic facilities, and a shared territory. As private ownership creeps into the public domain, materials and products dominate to create a new order and, equally, to exclude.

Standard models of separation begin to crumble. Conventional land use and zoning, which define mono-functional spaces, become inadequate. The gaps thus left need to be

filled by new urban conditions that are sustainable and inclusive. The infrastructure underbelly, urban management, and systems will influence space, form, scales, and territorial imperatives.

As the omnipotence of architecture withers away, its isolation makes no sense beyond property boundaries or movie theatres. Though possessed of its own internal logic, architecture has become an irrational exception to its context. It must not be imprisoned by its exclusivity. Formalism is a crutch, and mobility can only come out of stylistic interpretation – an ideology, even – inspired by the city and urbanism.

The architectural construct within which the new urbanism must develop is that, like Calvino’s ‘Invisible Cities’, there are many parallel and simultaneous cities that make up the larger metropolis. Unlike them, these need not live only in the imagination. The new urbanism believes that the global city cannot conform to a single template, and that every city reflects its own unique multiplicities. It acknowledges diversity, differences, conflicts, and negotiations, as much as it seeks mediation and, to an extent, agreements. It seeks to accommodate and resolve contextual contradictions and spatial dichotomies. The excitement of space is at least as important as form. The form, in turn, is negotiated between the setting and modernization guided by technology. The many layers and textures make architecture granular.

Smaller spaces become microcosms of the city. The city’s very limitations and idiosyncrasies become the last bastion of individuality in an increasingly power-driven society. These concepts grow and mature in the cellars of the imagination, only to emerge stronger and more potent given the chance.

The contemporary urban landscape assumes significance parallel to historical references and collective memory, in an architecture of contextual multiplicity and specificity, applicable at all scales, from the urban to the local and the personal. The new urbanism integrates architecture with development. It is certainly not a celebration of irresponsibility. It does not add to the apparent confusion. It works towards clarity.

S.K. Das

25th July 2004

A HOUSING

PARADIGM OF

SPECUALTION

A Context of Design

Two opposite conclusions can be drawn regarding the role of design and spatial planning contributing to an urban housing strategy and its realization. The dominant and official view holds that design and physical planning have little role to play since the emphasis has shifted on to housing by people and the role of government to that of facilitator. The built form and even the image of the city is seen as a consequential phenomenon, something that would somehow emerge out of a play of market forces rather than be conceived systematically. As a result, cities become incoherent entities determined by a general level of popular taste and the whims of developers within a framework that is bureaucratic, proscriptive rather than pre-scriptive.

In opposition, one can argue that the challenges of spatial planning and design are more vitally complex today. The making of the built environment in response to new technological and economic considerations, culture and history, and the aspirations of common folks is what the architecture of housing and urban environment is really about. It allows a greater scope, from restructuring of the city to the laying out of neighborhoods that could establish a hierarchy of spaces and community formations analogous to the various systems that have always’ functioned in indigenous settlements throughout the world. The professional could take upon himself the task of deriving new’ urban coherence and continuity incorporating physical and spatial aspects at all levels that are necessary to establish a meaningful social context for housing.

Over the last decade, many Indian architects have begun to show respect for contextual design. The understanding of the context rests on various levels of city and community formation. For example:

-

The urban context or the context of the city and its development and what influence it bears on a specific site and consequently, the manner in which a project is inserted into a city and in return, the statement it should make to the city for altering strategies and encouraging new forms.

-

The context of the site with all its external linkages, neighbourhood relationships, and internal peculiarities of terrain, physical conditions and climate factors.

-

The context of the community that would form a neighbourhood, with implications of social economic and cultural groupings, service and facilities to support the community.

-

The sub-communities that need to be established as an essential means of desegregation into smaller scale groupings supported by corresponding level of services.

-

The context of the family and response through dwelling designs that are flexible, adaptable and incremental if necessary.

Each scale level has its own internal accountability in the articulation of space and built form while simultaneously making a set of demands (and in turn influencing) on the next scale level immediately higher or lower in the order. For example, private open spaces are seen as extensions of public space while dwelling facades and elements are as much a reflection of the internal organization of a house as of the demands arising from the nature of the collective space they surround. The spatial organization of facilities such as shopping areas or schools can make them a natural means of linkage between different parts of the neighbourhood.

General Principles

Although specific projects may have their own agendas, there are some underlying principles of greater significance.

In dealing with change, there is an ethical basis for handling of areas. At a minimum, these have to do with access, equity, integration and linkages in order to promote a social city.

Notions of land use and density must be based on social development opportunity and not be a consequence of floor area ratio. Higher density, concentration, and diversity of functions are dynamic aspects of urbanity.

In the face of rapid change there is always a danger that the city gets fragmented. Fragmentation occurs in a two-fold way. On the one hand it can involve a process of disintegration: a well established structure is disrupted and broken into pieces, which show no interconnection with one another. On the other hand, fragmentation can be a process of piecemeal development. The result of such a development presents a spatial appearance which lacks coherence, structuring and integration.

Coherence in design represents a movement towards a certain unity and completeness: things are interconnected through a spatial structure which is legible because it obeys certain logic.

Spaces must provide for a multitude of social life. Layering of functions and meaning is a matter of design. These meanings cannot be derived from land use and zoning decisions.

1. Charles Correa, “Transfers and transformations” in Charles Correa-Architect in India and Hasan-Uddin Khan, A Mimar Book; Concept Media Ltd. and Butterworth Architecture, 1984,

2. Herman Hemberger, “Shaping the Environment: Architecture for People” edited. by Byron Mikellides, Holt,Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1980.

References

“Traditional housing environments have an inherent logic of resilience, but need to change in response to new infrastructure, networks, and communications. Design initiatives by architects have questioned design assumptions and solved contextual problems in ways that deserve more attention than has been given. Community- based urban interventions and activism constantly raise vital questions and demand new strategies.

There is a need to understand existing specificities in all their multiplicity, and design long-term resilient housing forms, typologies and fabrics that will allow these specificities to flourish and change, instead of a single global template determining undifferentiated and standardized solutions.”

A NEW ARCHITECTURE OF HOUSING